“A society does not ever die ‘from natural causes,’ but always dies from suicide or murder—and nearly always from the former.” — D. C. Somervell.1

À propos of nothing, I have found myself wondering recently what it would be like to live through a collapse. Would I see it coming? What would be the signs?

A number of times in human history, a society has gone from a relatively high level of sociopolitical complexity to a much lower one—rapidly, within the span of a few decades. This is what we will call collapse. Collapse manifests as a lower degree of social differentiation and economic specialization, less centralized control, less behavioral control, less investment in art and monuments, a lower flow of information within society, less sharing and trading of resources, a lower degree of social coordination and organization, and territorially smaller political units. And a lot of people probably starve, if they don’t meet more violent ends.

Collapse is a fate that befell at least the Western Zhou empire; the Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley; medieval Mesopotamia in parts of the Abbasid caliphate, including the Anarchy at Samarra; the Egyptian Old Kingdom; the Hittites; the Minoans; the Mycenaeans; the Western Roman empire; the Olmecs; the Lowland Classic Maya; Teotihuacan, Monte Albán, and Tula in the Mesoamerican highlands; Casas Grandes in northern Mexico; the Chacoans in what is today New Mexico; the Hohokam in southern Arizona; the Eastern Woodlands civilization, including the Mississippians centered on Cahokia in today’s East St. Louis; the Huari and Tiahuanaco in Peru; the Kachin of highland Myanmar, who oscillated between complex and egalitarian social forms as described by James C. Scott; and the Ik of northern Uganda, who have simplified society to such an extent that they allegedly reject familial bonds, although this has been disputed.

Collapse has happened often enough that it is not likely to be a series of flukes, but a general feature of human social organization. Not every society eventually suddenly collapses; it may be the case that when one does it is because some particular conditions obtain. What are those conditions? Can we come up with a general explanation? And while the subject is interesting as a pure matter of social science, we all want to know: could it happen here?

The GOAT on the topic of collapse is archeologist Joseph Tainter. His 1988 book The Collapse of Complex Societies weaves together historical and prehistorical fact, an insistence on explaining the cross-sectional variation, rigorous theorizing including an embrace of marginal analysis, and generally great social scientific judgment.2 It is a tour de force. If you want to understand why it has lived rent-free in my head for the last few months, as several friends can attest, read on.

Why complexity?

If we’re going to understand why societies sometimes spontaneously simplify, we must first have a solid theory about why they become complex in the first place. In both a historical and analytical sense, simple human societies arise first. These simple societies are highly egalitarian and non-hierarchical. Why do they move toward greater hierarchy, stratification, inequality, and complexity?

There are broadly two views on this question. One view is dominated by class conflict. The state reflects domination and exploitation based on divided interests. A ruling class coercively subjugates the population out of greed and selfishness. Marxists are not the only exponents of this view, but they are perhaps the most vehement, viewing society as sharply divided between workers who engage in social production and elites who appropriate the output. Of course, subjugation of subpopulations happens—American slavery is a gruesome example. The pure class conflict view is that subjugation explains the entirety of society, which is composed of ruling elites and subject populations.3

At the other end of the spectrum are integrationist or functionalist views, which are based on shared interests between members of society. Even an egalitarian society is going to face problems, and many of these problems are most readily addressed by creating some form of hierarchy and social division of labor. For example, limited water resources may require the creation and maintenance of an irrigation system, including the need to mobilize and direct labor. The threat of invasion may require the establishment of military defense, including a command and control system. In general, society faces some problem, which requires the creation of public goods, which requires the creation of administrators, who are rewarded for realizing the benefits of centralization. Complexity solves social problems and serves population-wide needs.

Tainter adopts a moderate position, one that leans integrationist but also includes a role for class conflict. Complexity in society does exist to solve problems and provide benefits to the populace. And yet, “compensation of elites does not always match their contribution to society, and throughout their history, elites have probably been overcompensated relative to performance more often than the reverse.” Public choice considerations mean that even if complexity arises to solve broad-based social problems, the ultimate distribution of the benefits can be influenced by greed and power. “Integration theory is better able to account for distribution of the necessities of life, conflict theory for surpluses.”4

Although the distribution of the social surplus is not always fair, in what follows, the role of complexity in society as a problem-solving mechanism is what is most important. Without this foundation, collapse is no big deal, or good, or perhaps it is even the ascension of society to a Marxist anarcho-primitivist Utopia. We can sympathize with this view when true subjugation is occurring, while recognizing that, in the general case, complex society exists to solve social problems.

Collapse theory

There are many non-general or underspecified theories of collapse. Tainter goes through these exhaustively, but I’ll run through a few of them that deserve special mention.

Depletion of a vital resource. These explanations are popular with environmentalists, and feature strongly in books like Jared Diamond’s Collapse (which came out 16 years after Tainter’s). Tainter has contempt for depletion arguments as a causal mechanism, because, as we have just discussed, the complexity of society exists to solve problems including resource depletion. What about all the times that resources are effectively stewarded? Is it not true that for most resource/society/time period combinations, societies do just fine in not collapsing due to resource depletion? Depletion arguments don’t explain the cross-sectional variation, why sometimes societies effectively manage resources and other times they don’t. “If a society cannot deal with resource depletion (which all societies are to some degree designed to do) then the truly interesting questions revolve around the society, not the resource. What structural, political, ideological, or economic factors in a society prevented an appropriate response?”

Insufficient response to circumstances. Suppose a society is faced with a problem, perhaps depletion of a vital resource. Not responding to the problem can lead to collapse. But why does this insufficient response occur? Often, historians have argued that a society is a lumbering dinosaur, a runaway train, or a house of cards—static, incapable of changing directions, or fragile. While these theories rightly recognize that collapse depends more on the characteristics of a society than on its stresses, they too do not explain the cross-sectional variation. After all, societies sometimes do respond to serious problems in dynamic, agile, and robust ways. What explains why they would suddenly stop doing that?

Elite mismanagement. To some extent, exploitation and misadministration is a normal feature of hierarchical societies. Even if we take a class conflict view, shouldn’t elites, if they are even slightly rational, view the support population as a vital resource? If so, then the problem becomes the same as in the “vital resource” explanation given above. If we blame elite greed and self-aggrandizement, why should we assume that this is variable, and if it is variable, how can we explain it? Again, allegations of mere elite mismanagement do not explain the cross-sectional variation.

Tainter discusses many other theories, and holds particular contempt for decadence theories of collapse, which are common in the literature, but which he considers mystical and non-scientific.5 They too do not explain the cross-sectional variation.

So what does explain the cross-sectional variation? Tainter develops a theory based on diminishing marginal returns. Diminishing marginal returns are ubiquitous in economic analysis and indeed in life. The first bite of a pecan pie is sublime; the 20th may be cloying. The same principle operates in countless domains. The exceptions are usually temporary, yielding increasing returns to scale over some range, but eventually succumbing to diminishing returns. Tainter argues that there are diminishing returns to complexity itself.

Society adds complexity to address problems and stresses. In an American context, this is easy to understand. When drugs are unsafe, we increase the stringency of FDA review. When federal projects are too polluting, we pass the National Environmental Policy Act. When there is an oil shock, we create a federal Department of Energy. Terrorist attack? Department of Homeland Security. Financial crisis? CFPB.

This added complexity accumulates. As it does so, it requires resources—Tainter emphasizes energy and fiscal resources6—to maintain. Often, the resource demands of one piece of complexity necessitate more complexity, as when a higher tax rate necessitates new resources to be put into legitimization and coercion. The complexity accumulates as a system. At first, the cost-benefit ratio of this added complexity is very favorable, and the marginal benefits are high. As more complexity is added, the marginal benefits diminish, then go to zero, before turning negative.

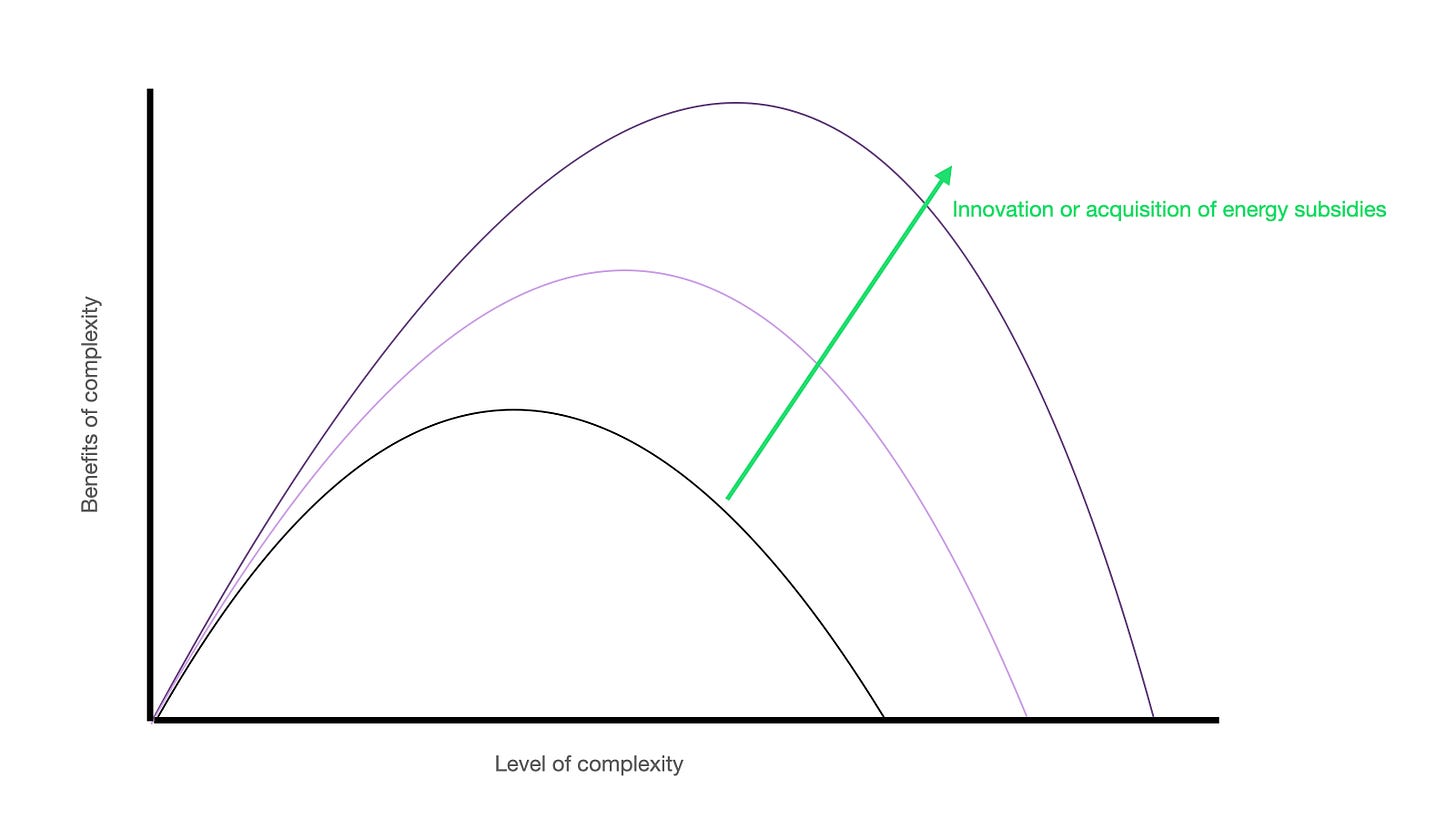

A society that is past complexity level C2 on the graph above is in a very precarious position. Many members of a society at C3 would rather be at C1, although there is no direct path there because, as just noted, the complexity itself behaves as a system. As Tainter puts it, “when the marginal cost of participating in a complex society becomes too high, productive units across the economic spectrum increase resistance (passive or active) to the demands of the hierarchy, or overtly attempt to break away.” He emphasizes that this can be equally true across the income spectrum; everyone from the peasants to the merchant class to the nobility will be tempted to defect from the current system. “A common strategy is the development of apathy to the well-being of the polity.”

The situation can spiral out of control quickly. An overtaxed peasantry may put up little resistance to invaders. Increasing costs can make public services unsustainable. An increasing share of resources may have to be devoted to legitimation and control. The economy weakens. The ability or desire to meet new challenges evaporates. Collapse is only one new problem away.

According to Tainter, collapse can temporarily be prevented by the acquisition of a new technological capability or energy subsidy. With the additional resources afforded by the technology or subsidy, societies can support a higher degree of complexity. I think Tainter’s graphical representation of this point gets it wrong, but the image below from Ben Reinhardt accurately captures how I envision it.

Even this possibility, however, does not change the logic that the returns to complexity eventually diminish and go negative. If a society keeps increasing its level of complexity, it will inevitably get to a point at which the population would prefer less complexity.

Let’s think about the Roman Empire

Although Tainter tests his theory against all cases of societal collapse, he goes in depth on three cases. I will focus in particular on one of these, the case of the Western Roman Empire, since it apparently features so prominently in the minds of so many.7

Under the Republic, Rome had a policy of expansion, which may have been driven by internal needs, like a lack of opportunity for many citizens at home. Conquered territories were looted. Conquest paid for itself. Expansion provided so many resources that, during the late Republic, direct regular taxation of Roman citizens in Italy was abolished. “In 167 B.C.” explains Tainter, “the Romans seized the treasury of the King of Macedonia, a feat that allowed them to eliminate taxation of themselves.” And “after the Kingdom of Pergamon was annexed in 130 B.C. the state budget doubled.”

Tainter views the initial looting of newly conquered territories as an energy subsidy. After all, the economy was mainly agricultural, and agricultural products are basically stored sunlight. The treasure that was looted in each new conquest was the conversion of many years’ worth of agricultural products into other forms of wealth, and you can still view it as embodied energy to some extent. Yet the seizure of many years’ worth of accumulated sunlight, so to speak, cannot be matched by taxation of annual agricultural output, one year’s captured sunlight. The energy subsidy continues only as long as expansion does. Meanwhile, the administration costs of an expanding domain increase at least in proportion to the size of the controlled territory, and likely faster.

Under the Principate, the empire began to feel unwieldy. Expansion slowed and eventually halted. Claudius conquered Britain, and Trajan conquered Dacia, but Hadrian ended expansion and gave up recent conquests in the Middle East. The slowdown and reversal of expansion affected the Empire’s finances. After the initial looting of newly conquered territories, regular tribute and taxation were imposed, but these did not yield the same resources for the Romans as the accumulated treasure brought home in the initial conquest. This reduction of revenue created fiscal problems for the Emperors, who needed to pay for the military, the administration of the Empire, public works, and a hefty public dole.

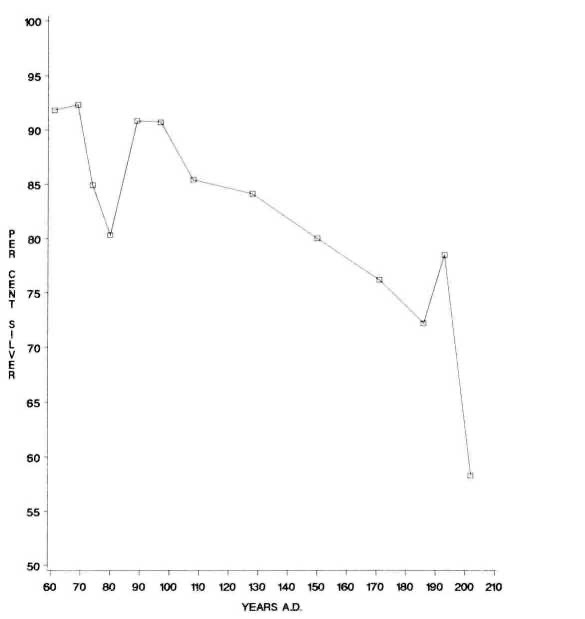

The fiscal situation briefly stabilized under Antoninus Pius, but, under his successor Marcus Aurelius, new stresses surfaced, including 15 years of plague and wars with Germanic tribes. Commodus and Septimius Severus continued the policy of currency debasement of the denarius that had been initiated as far back as Nero. This naturally resulted in inflation, which continued through the 200s, by the end of which the currency was thoroughly debased. The economy was in shambles. To a considerable degree, Rome reverted to a non-monetary economy: Aurelian conscripted tradesmen to build the walls around Rome, and Diocletian collected taxes in the form of supplies directly usable by the military instead of in money.

Although some of the early years of the Principate were relatively stable and prosperous, without a continued energy subsidy from expansion, the Emperors felt the weight of the Empire’s complexity. This came to a head in the Crisis of the Third Century, during which the Empire almost collapsed.

Under the Dominate, established by Diocletian, the Empire increased its degree of authoritarianism. This staved off collapse, at the cost of requiring an increase in social complexity. The sizes of both the military and the civil administrations doubled. Taxes were crippling; rates had to go up to account not only for increased spending but also because the tax base was shrinking. The Empire instituted rigid control of individuals and their output. A system of serfdom was imposed to prevent peasants from abandoning the land. Many occupations became hereditary, with soldiers’ sons required to be soldiers, and so on.

This increase in authoritarianism in the Dominate illustrates Tainter’s point that the complexity of a society increases as a system. The choice facing Diocletian and his successors was to collapse or to intensify social control. Each intensification of social control required yet more social complexity, for example systems of coercion to enforce compliance. The burden of it all continued to grow.

This growing complexity and its negative marginal returns resulted in apathy and defection:

“Contemporary records indicate that, more than once, both rich and poor wished that the barbarians would deliver them from the burdens of the Empire. While some of the civilian population resisted the barbarians (with varying degrees of earnestness), and many more were simply inert in the presence of the invaders, some actively fought for the barbarians. In 378, for example, Balkan miners went over en masse to the Visigoths. In Gaul the invaders were sometimes welcomed as liberators from the Imperial burden, and were even invited to occupy territory.”

We therefore come to Tainter’s conclusion that “the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West cannot be attributed solely to an upsurge in barbarian incursions, to economic stagnation, or to civil wars, nor to such vague processes as decline of civic responsibility, conversion to Christianity, or poor leadership.” Rather, the collapse was due to a high and increasingly costly level of social complexity.

Minor objections

A few quibbles.

Tainter published his book in 1988, and many of his background assumptions about the state of the world no longer hold. This is particularly true regarding energy. In the 1980s, like today, there was concern about transitioning away from fossil fuels, but the rationale was somewhat different—people were concerned that the oil was running out.

In a world that is running out of fossil fuels, there is a close parallel to the end of Roman territorial expansion. Just as Roman conquests yielded many years of accumulated solar energy as loot, fossil fuels represent millions of years of accumulated solar energy. If the Romans couldn’t manage the shift from accumulated surplus energy to real-time energy harvesting without escalating complexity to the point of negative marginal returns, so too might we fail to make that transition. “A new energy subsidy is necessary,” writes Tainter, “if a declining standard of living and a future global collapse are to be averted.”

In 2024, however, this does not seem like a serious problem. We are not running out of fossil fuels. Advances in fracking mean we have plenty of them for the foreseeable future. Rather, the problem is a more mundane (though still concerning) one of resource management, where the resource in question is our atmosphere and oceans. We still have to transition away from fossil fuels because of climate change, but this is a governance problem of the kind we have faced before, as when we globally banned ozone-depleting substances. Climate change is a more costly problem than the hole in the ozone layer, but structurally, in Tainter’s framework, it is different from the end of an energy subsidy.

In 2024, we also have energy tools that did not exist in the 1980s. Solar panel and battery prices have fallen by 97+ percent since 1988. The same drilling and subsurface engineering improvements that have driven down the cost of oil and gas in the shale fields could also make geothermal energy viable basically anywhere. After all, geothermal works in Iceland, and everywhere is Iceland if you drill down deep enough. And, of course, clean nuclear energy has existed since the 1950s, although in terms of construction costs the industry has experienced negative learning since the 1970s.

The problem for the energy transition is not the loss of an energy subsidy, but rather that the accumulated complexity makes it expensive and slow to deploy the clean sources. Obstacles like the National Environmental Policy Act and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission are a much more significant problem than lack of technology. With current and soon-arriving technology, we could have much more energy abundance than at any time in human history. Industrialists like Casey Handmer believe we will soon have enough clean energy to end water shortages in the Western US and produce non-crustal hydrocarbon fuels at scale.

If we are not as committed as Tainter is to the modern analogy to fossil fuels running out, then there is less need to frame the historical collapse discussion in terms of energy subsidies. Although energy is a critical resource, it is not the only one. Simply thinking of the problem in terms of resources in general is adequate, without any loss of power for the underlying theory.

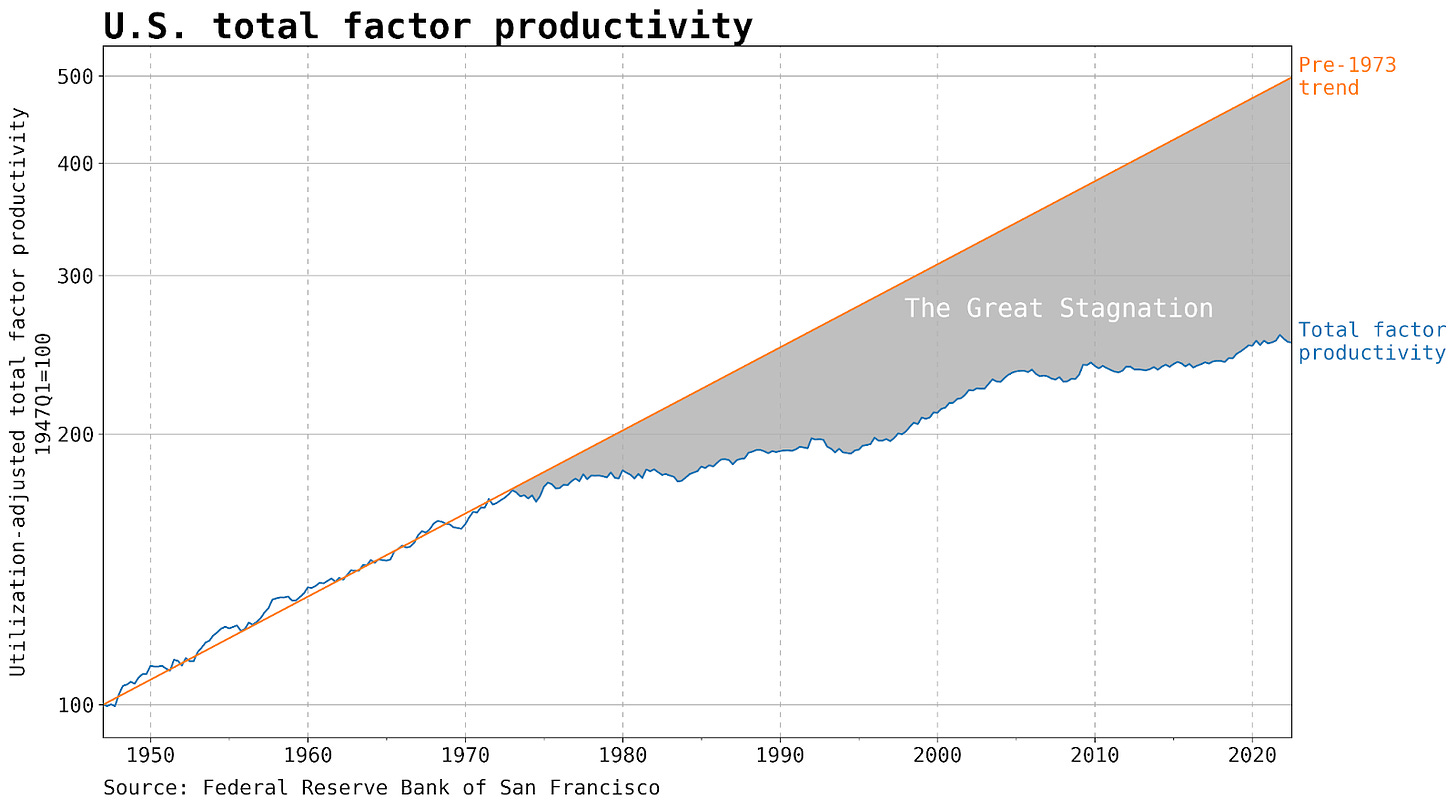

Separate quibble: Tainter believes in declining marginal returns to basically everything, including research and development. This puts him firmly in the mainstream in innovation economics, echoing recent papers like Benjamin Jones on the “burden of knowledge” and Bloom et al. on ideas getting harder to find. These are all good economists, and I have no real quarrel with their empirical work narrowly construed, but I think much of the interpretation is wrong.

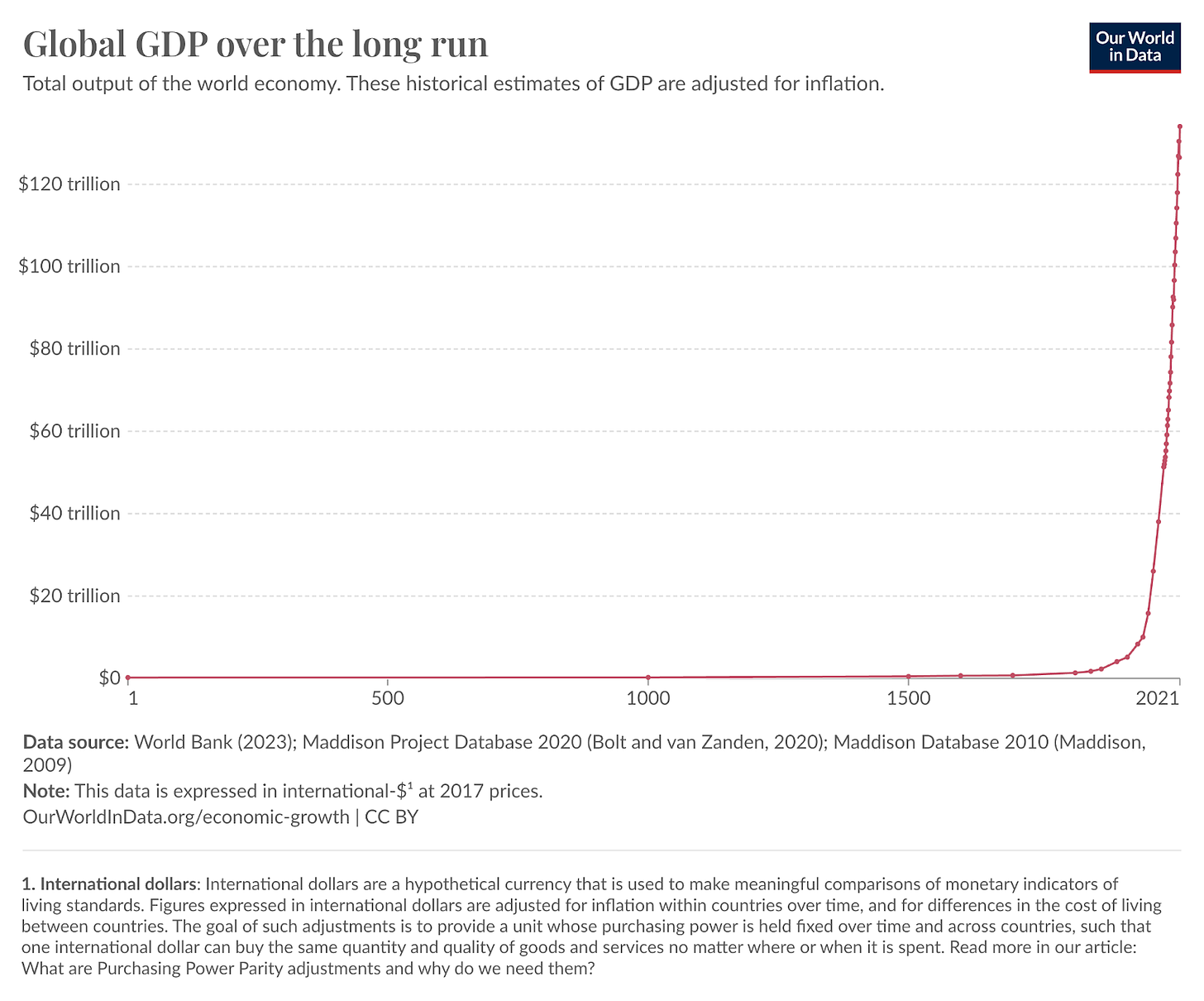

Availability of new ideas has a funny relationship with economic growth. As Jason Crawford has noted, ideas were very easy to find in the Stone Age. Modern humans went over 200,000 years without inventing the wheel. These were people who were biologically identical to us. They lived in a completely stagnant economy with no increase in GDP per capita from generation to generation. Once discovery started to happen, it built on itself exponentially. New ideas made it easier to find new ideas. Growth surged.

Moreover, even today, it’s clear that some technologies enable new discovery paradigms. Computing and molecular biology come to mind. A single graduate student in biology in 2024 can sequence genomes, edit them, and create novel organisms—activities that enormous teams of scientists with huge budgets could not do a few decades ago. It’s a golden age. Perhaps LLMs too will enable smaller and less-experienced teams to achieve bigger breakthroughs than what was possible before. There are many respects in which the burden of knowledge is lower today due to abstraction or gains from trade. Most computer programmers no longer really need to know how computers work, which was not true in the past.

Instead of diminishing marginal returns to innovation, I think it’s much more plausible that Tainter’s accumulated complexity is behind slowing rates of both economic growth and measured research productivity. I’ll have much more to say about this in the future, including some arguments I am not deploying here, but for now I just want to flag that my enjoyment of Tainter’s book does not imply endorsement of his analysis of innovation.

My final quibble is that Tainter appears too eager to portray collapse as a logical choice.

“To the extent that collapse is due to declining marginal returns on investment in complexity, it is an economizing process. To a population that is receiving little return on the cost of supporting complexity, the loss of that complexity brings economic, and perhaps administrative, gains. Again, one is reminded of the support sometimes given by the later Roman population to the invading barbarians, and of the success of the latter at deflecting further invasions of western Europe.”

Collapse, in other words, is bad for most elites and of course for modern historians with a “civilizationist” bent. But it can be good for the support population, many of whom are peasants involved in primary food production, who are relieved of the crushing weight of administrative bloat after a fresh societal collapse. Maybe the majority of people can be better off.

While I appreciate the anthropologist’s value neutrality, this seems unlikely to me. One reason is raised by Tainter himself: “One ambiguity in this view is the major loss of population that sometimes accompanies collapse. The Maya are a classic case in point. How advantageous can the Maya collapse have been if it resulted in major population loss?” He argues that it’s possible that depopulation may have preceded the Mayan collapse, or that the population may have migrated to the surrounding area.

Maybe. Regardless of the specific evidence on Mayan depopulation, I suspect that just as the complexity of a society grows as a system, it collapses as a system. There is no reason to believe that simplification stops at the optimal point. In my mind, there is a family resemblance to financial contagion. Financial crises have macroeconomic effects that are out of proportion to the initial shocks or failures. Even if we believe that a particular financial firm deserves to fail, that doesn’t mean there will be no innocent victims, because the financial system contracts as a system. Similarly, supply chain difficulties during the pandemic, although minor in the grand scheme of things, gave us a taste of what bigger shocks could look like. They look like they would spill over into even larger disruptions. It may be in peasants’ interest for society to decomplexify to some degree, but once the process gets rolling, it may continue beyond the point where they benefit.

Thankfully, Tainter is clear that a collapse today would not be so rosy as he maintains past ones were. “Collapse for such [highly industrialized] societies would almost certainly entail vast disruptions and overwhelming loss of life, not to mention a significantly lower standard of living for the survivors.” In part, this is because “much of the population does not have the opportunity or the ability to produce primary food resources.”

More generally, we might say (Tainter does not) that many more people today are in some sense elites because their livelihoods are a product of social complexity, even if they are not government administrators themselves. If you have to quit your job as an ML researcher to become a primary food producer, that sounds bad, no matter how severe the tax burden is and even if you have the knowledge and skill to succeed at food production. I’d be disappointed not to be a Chief Economist anymore, but I don’t think they have those in simple societies. Even the 1.4 percent of the labor force that is involved in agriculture works in a highly mechanized and globalized way, dependent on global supply chains for access to tractors, fuel, and fertilizers as well as markets for their products. The productivity hit they’d take from collapse would be enormous. In the modern world, we all have a stake in not collapsing that greatly outweighs, say, our tax burdens. If we collapse, it won’t be rational.

Relatedly, Tainter points out that the nature of collapse would be different in the modern era. At our point in history, there are no isolated states. We have not had any collapses of individual states in Europe since the fall of Rome, because any collapsing state would be quickly taken over by one of its neighbors. Europe, and virtually the whole globe, is fully spanned by complex societies. Because members of these “peer polity systems” do not wish to be invaded, they “tend to evolve toward greater complexity in a lockstep fashion as, driven by competition, each partner imitates new organizational, technological, and military features developed by its competitor(s).”8

As a product of its time, some of this analysis is driven by Cold War dynamics. But it seems correct, especially if Pax Americana is in doubt, that countries are forced by defense and geopolitical considerations to complexify as their neighbors do. The world today is one system. Tainter doesn’t focus too much on supply chains, but they would bolster his argument. Imagine that global trade in a few basic commodities like oil and fertilizer broke down. A lot of other production would halt as producers starve to death or otherwise lack the resources to continue. This would collapse other trade linkages. The conclusion is a scary one. “Collapse, if and when it comes again, will this time be global. No longer can any individual nation collapse. World civilization will disintegrate as a whole. Competitors who evolve as peers collapse in like manner.”

Application to current conditions

“The people desire disorder.” – The Book of Poetry

Can we apply Tainter’s ideas to contemporary America? It’s unsettling to do so, but we must. It’s hard to disagree with a few propositions that, with collapse theory in mind, should give us pause.

Sociopolitical complexity is high. I’m not the only one who thinks so. Here’s Steven Teles from 2013:

“In recent decades, American politics has been dominated, at least rhetorically, by a battle over the size of government. But that is not what the next few decades of our politics will be about. With the frontiers of the state roughly fixed, the issues that will define our major debates will concern the complexity of government, rather than its sheer scope.

“With that complexity has also come incoherence. Conservatives over the last few years have increasingly worried that America is, in Friedrich Hayek's ominous terms, on the road to serfdom. But this concern ascribes vastly greater purpose and design to our approach to public policy than is truly warranted. If anything, we have arrived at a form of government with no ideological justification whatsoever.

“The complexity and incoherence of our government often make it difficult for us to understand just what that government is doing, and among the practices it most frequently hides from view is the growing tendency of public policy to redistribute resources upward to the wealthy and the organized at the expense of the poorer and less organized. As we increasingly notice the consequences of that regressive redistribution, we will inevitably also come to pay greater attention to the daunting and self-defeating complexity of public policy across multiple, seemingly unrelated areas of American life, and so will need to start thinking differently about government.”

Nicholas Bagley, 2021:

“Inflexible procedural rules are a hallmark of the American state. The ubiquity of court challenges, the artificial rigors of notice-and-comment rulemaking, zealous environmental review, pre-enforcement review of agency rules, picayune legal rules governing hiring and procurement, nationwide court injunctions—the list goes on and on. Collectively, these procedures frustrate the very government action that progressives demand to address the urgent problems that now confront us.”

Moreover, we often choose more complex solutions for public choice reasons. If we had instituted even a conservatively estimated carbon tax in the 1990s, we would be three decades into leveraging the power of the market to drive investment in clean technologies—this seems like it would have worked out well and been relatively simple.9 But a carbon tax was not popular with the public and it burdened many special interests, so we relied instead on an enormous and farcical patchwork of regulations, incentives, and mandates to drive the energy transition. Special interests like the incentives, even if they would also, as clean energy producers, do well under a carbon tax. While subsidizing clean energy production, we continue to restrict its supply through burdensome permitting rules. A carbon tax coupled with permitting reform would be both simpler and more effective than what we have today.

For Rome, currency debasement was a sign of fiscal stress arising from excess complexity. In the United States, seigniorage revenue is not as fiscally important as borrowing is.10 The debt data is worrisome. CBO estimates the federal government will run a deficit greater than or equal to five percent of GDP basically forever, rising to over nine percent of GDP by 2054, when federal debt held by the public will equal $146.3 trillion. Narrow questions of affordability are beside the point—Japan has a much higher debt-to-GDP ratio, so it’s reasonable to believe that we are not in any immediate danger of a default. The more serious issue is that, like Rome, our political system seems to be incapable of bearing the short-term pain of spending cuts or tax increases.11

Complexity in the American system feels like a one-way ratchet. We add but we do not often subtract. Tainter’s contention that sociopolitical complexity grows as a system seems correct in the American context.

Our economy is stagnating. American total factor productivity growth, the broadest and best estimate of economic growth, has stagnated since around 1973.

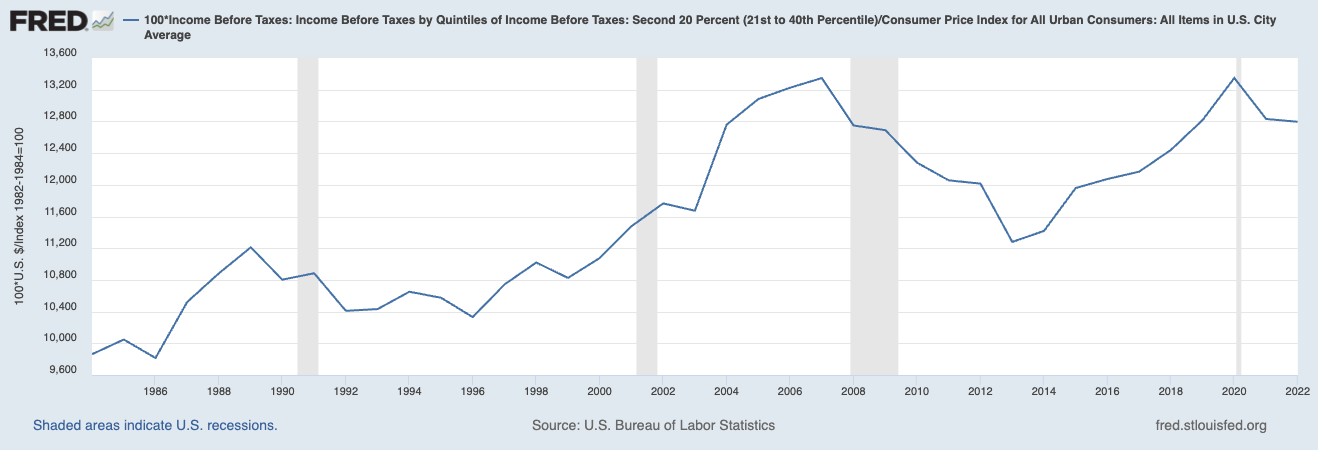

The brunt of stagnation has not been evenly distributed. The rapid increase in computing power over the past 50 years has made software developers, who are complements to computing power, valuable. Doctor salaries are doing fine, driven by medical supply restraints. White collar professionals like investment bankers continue to do well. It is the bottom half of the income distribution that has borne the burden of a stagnant economy.

If we look at, say, real pre-tax incomes in the second quintile, this group had essentially zero growth in pre-tax income between 2004 and 2022, while the top quintile had about 19 percent cumulative growth. The 2008 recession was deep for them. There are many caveats to be made—is pre-tax income the right metric,12 people do not stay in the same quintile throughout the life cycle, household sizes are changing, etc. Fine. It doesn’t change the basic idea that American stagnation has been highly uneven across the income distribution and has hit the bottom half harder than the top half.

There has been a wave of nihilistic populism. On both the left and the right, demagogues and useful idiots are tapping into the public's dissatisfaction and distrust of our political and social systems. On the right, I interpret this populist wave to be mostly non-cognitive. Do conservatives actually believe vaccines don’t work and that we should let Vladimir Putin roll over Ukraine? Do they really believe the 2020 election was stolen? Or do they simply like to espouse positions to antagonize liberal opponents? It seems that what they really demand is “not this.”

Among some on the left, there appears to be opposition in principle to enforcing laws against property crime. Defund the police, overthrow capitalism. October 7 denialism and Hamas apologia. This far-left populism is equally destructive as the right-wing version, and it is possibly less non-cognitive and more sincere.

Tainter says that when complexity reaches a high level, people start to defect by developing “apathy to the well-being of the polity.” With the caveat that neither Twitter nor college campuses are real life, at least for a subset of the population, we are far beyond apathy. Hostility is a better word.

We should consider the possibility that Tainter-style dynamics are at play. We have allowed a great deal of sociopolitical complexity to build up over the past several decades. We are deep into the range where the marginal value of complexity is negative, where it is inhibiting value creation more than it is solving problems. This has gone on for a few decades, yielding stagnation and resentment. Most elites, following the path of least resistance and mostly concerned for their narrow well-being, have done nothing to slow or reverse the buildup of complexity. At least some portion of the population would welcome the barbarians.

If Tainter’s theory is correct, America is a ticking time bomb.

ρ(doom,abundance) < 0

“Once a complex society enters the stage of declining marginal returns, collapse becomes a mathematical likelihood, requiring little more than sufficient passage of time to make probable an insurmountable calamity.”

Yikes.

Although most aspects of Tainter’s theory are persuasive and straightforward application to the contemporary United States is somewhat frightening, there are reasons not to panic. There are no modern industrial societies in Tainter’s data, and it’s not clear that the dynamics would be identical to what he proposes. New energy technologies are poised to create more energy abundance than we’ve seen at any point in history. And collapse can take a long time: “As seen in the cases of the Romans and the Maya, peoples with sufficient incentives and/or economic reserves can endure declining marginal returns for centuries before their societies collapse.”13

It’s fair to call the risk of American or global economic collapse speculative. When someone tells you to take extraordinary measures to address a highly speculative risk, beware.14 A happy coincidence is that we need not do anything exotic here. As it turns out, the set of policy actions one might take to stave off collapse is virtually isomorphic to the set one might take, on the flip side, to produce abundance.

We need earnest culling of net-harmful social complexity. We need new resource subsidies to become available through deploying new technology.15 We need to make it easier to deploy and iterate at scale. We need the government to act effectively and earn societal trust. We must eliminate low-value bureaucracy and procedure. We need to make sure that prosperity is widely shared, not only through transfers but in a primary income sort of way. The no-collapse agenda effectively is the abundance agenda.

There are plenty of reasons to prioritize an abundance agenda without resorting to concerns about collapse. While we are far from an elite consensus needed to drive change, there is already a cluster of people working on abundance, progress studies, and supply-side politics.16 A prosperous society is its own reward. I want to live in a world of material plenty and technological wonder.

And yet, at least for me (and maybe now also, by the end of this essay, for you), the risk of collapse provides some additional motivation. It’s not fear of imminent demise, but rather a clear-eyed understanding of the social dynamics. After studying collapse theory, we know better how the system works, and we know what needs to be done. Let’s go root out some low marginal-product complexity.

This quotation, or a paraphrase, is frequently attributed to Arnold Toynbee, but it actually comes from an editor’s note written by Somervell at the end of Chapter XV in the abridged version of the first six volumes of Toynbee’s A Study of History.

How many other anthropology PhDs engage with the work of Mancur Olson?

North Korea probably comes closest today to being a pure class conflict state.

What explains the cross-sectional variation in where individual societies fall on the spectrum between class conflict and integrationism? This is not just a question of why some governments are more or less authoritarian, for many autocracies have economic policies that are similar to democracies, behaving, as Tainter suggests, as integrationism predicts at the core. Nobody has read it, but I developed a theory of this based on what I call “metapolitical transaction costs” in Chapter 1 of my dissertation.

Even the latter he often views as embodied energy.

I’m more of a Mongols guy, myself.

Counterpoint: Haiti has not recently been invaded.

There are, of course, complexities in designing a carbon tax, but it is far simpler than the alternative.

Since 2008, the US monetary base has increased by around $5 trillion, but federal debt has increased by about $24 trillion.

Score a point for Buchanan and Wagner.

Post-tax income includes certain kinds of government transfers, which contribute to spending power and well-being, but they might not contribute to a sense in the recipient that society is working for him or her in the same way that pre-tax income growth would. It’s notable also that transfer payments (“the dole”) also grew throughout the decline of the Roman Empire. For collapse analysis purposes, pre-tax inequality seems best. In any case, if you must know, real post-tax income for the second quintile increased by 7 percent cumulatively from 2004 to 2022, still pretty slow growth.

Less encouragingly, Tainter adds, “(This fact, however, is no reason for complacency. Modern evolutionary processes, as is well known, occur at a faster rate than those of the past.)”

You all know exactly who I’m talking about.

Technology can also per se reduce social complexity. For example, even if large AI models never achieve general superintelligence, they can substitute for humans in a lot of low-value tasks, reducing the coordination costs that exist in large organizations. Advanced manufacturing solutions like nanotechnology could likewise abstract from a lot of complexity.

There are dozens of us!